In my final blog post I will be using the secondary sources I used in my second and third blog posts, Cronon’s “The Trouble with Wilderness” and Bergthaller’s “Fossil Freedoms: The politics of emancipation and the end of oil” and building on the analysis I made in the third blog post regarding ‘luxury’ as repetitive descriptive word for artificial islands. I will be focusing mostly on a specific picture with a sunset and a beach that advertises Banana Island on its website, but I will still show two other pictures where ‘luxury’ is used to describe the artificial islands before analyzing the third picture. Those two pictures are ones I have not used yet in any of the blog posts, but will create a foundation for the idea that this descriptive word is repeated, so that this blog post will have one like the third blog post did. The final picture I argue visually characterizes what ‘luxury’ means for artificial islands, and shows that nature is not ‘sublime’ in Qatar’s artificial islands as Cronon explains it is. The ‘luxury’ that is advertised shows that artificial islands use nature as decoration, as something beautiful, not ‘sublime’, and find human-made amenities more important. Artificial islands in Qatar are an exception to what Cronon explains people feel when they see something ‘sublime’ because the ‘sublime’ is literally covered up by the human-made facilities, as it is not what artificial islands promote when they promote ‘luxury.’

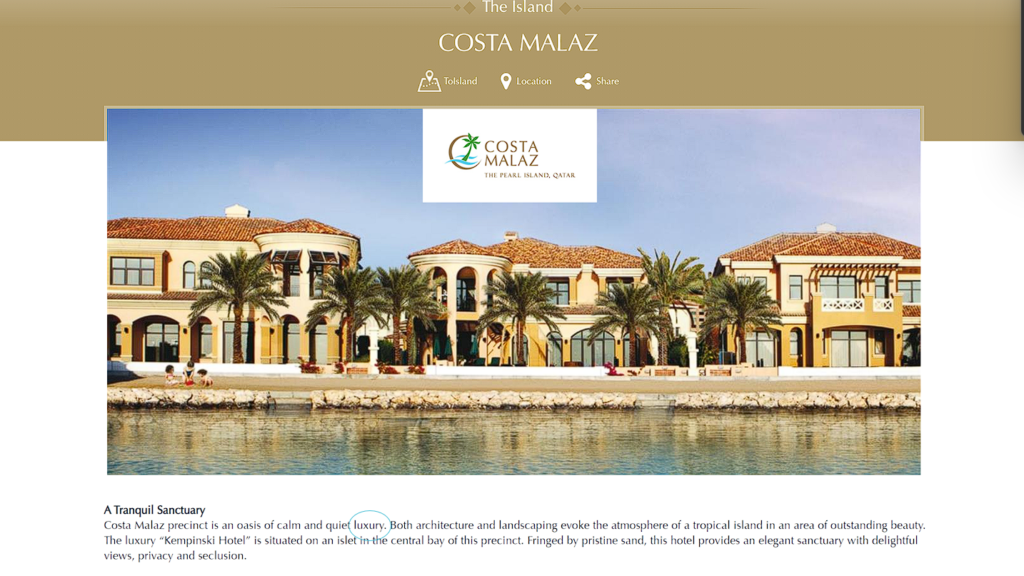

The first image I would like to use to highlight that artificial islands are promoted with the word ‘luxury’ is with this picture of Costa Malaz from The Pearl website. I have circled the word luxury on the image, and the photograph of the place itself already embodies what I will be analyzing in the photograph of a place on Banana Island. The image shows buildings next to one another, which are human-made amenities that needed petrol and energy to make. These human-made amenities are next to natural components such as the palm trees, the sky, and the river. However, as one can see from the descriptive paragraph it is not the nature that is being promoted, it is a decorative aspect of the place that makes it “an oasis of calm and quiet luxury.” Especially with the final words of the first sentence, “an area of outstanding beauty”, the idea of nature as only ornamental and visual is highlighted by the advertisement.

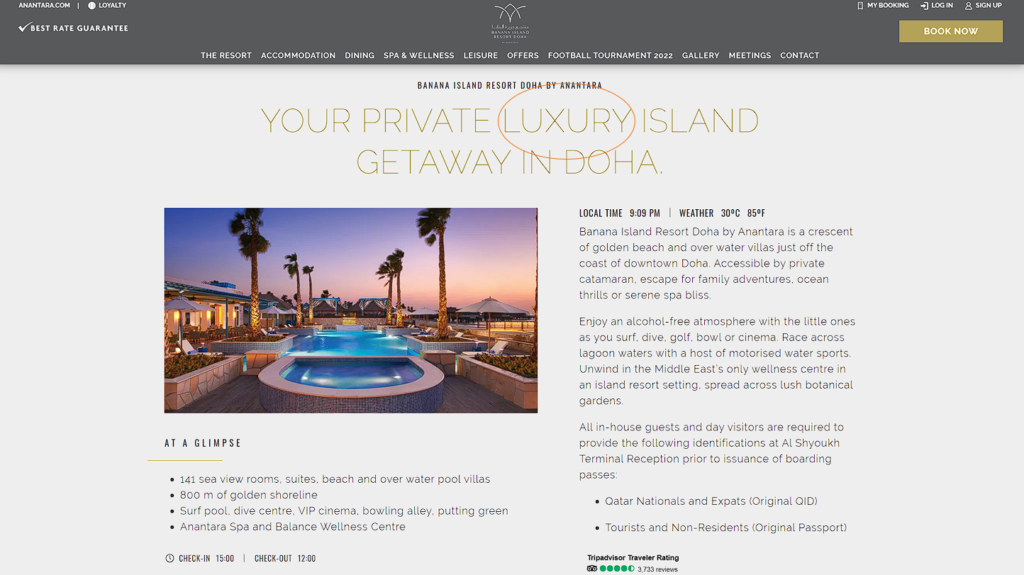

That idea is also highlighted in this second picture of the Banana Island website. From the words that describe the island on this picture it is possible to see that the ‘natural’ components of the island are being described so that a person will be able to imagine what the island looks like and see that it is a visually beautiful place: “Banana Island Resort Doha by Anantara is a crescent of golden beach and over water villas just off the coast of downtown Doha.” But the beach is not what is being promoted to the people who are reading the website. The actual parts of the island that serve as the reason why people should want to visit Banana Island are the human-made amenities. The website expresses that someone can “surf, dive, golf or cinema” and “race across lagoon waters with a host of motorised water sports.” Thus, even the action of being in something ‘natural’ such as the water is sold to people by virtue of the human-made “motorised water sports” rather than the ocean by itself.

The Banana Island website highlights gallery has different images on it, and one of them is the main photo I would like to analyze. It is not like the previous two I have spoken about in that there are some promotional words next to the image that I can analyze to explain how human-made aspects of the resort are more important than the ‘natural’. However, it is a poignant image which possesses a visual beauty to it that is very important to my argument because since it is part of the gallery, that means that it is an image the resort believes will attract people to the island even if there are no promotional words to create a sense of excitement about the place. Banana Island considers the beauty of this picture as a sufficient form of promotion. This is the photograph that I will be analyzing:

This image is of the “Q Lounge & Restaurant” in the gallery. This image has a boardwalk on it, with a well-lit area on the ocean with chairs and tables. There are also lights in the background and a structure on the right. Aside from this is a deep lilac hued ocean and a setting sky in the background. The main point of advertisement or attention on this image is the boardwalk in the middle, showing people that they can sit and eat while being next to this beautiful ocean. And even if this boardwalk was not there, one still has those lights on the ocean’s horizon and the buildings on the right as a distraction from the ‘natural’ aspects of the picture. If one were to take every single kind of distraction away, they would only see the ocean and the setting sky. This kind of image is what Cronon explains would be “those vast, powerful landscapes where one could not help feeling insignificant and being reminded of one’s morality” (Cronon 4). Seeing only the sky and ocean and especially ones of these lovely colors at sunset would be able to make someone feel that they contrast to the sky and ocean because they are miniscule while the thing that they are looking at looks so expansive. But a person looking at this picture would not be able to feel that because all of the human-made things in the picture take the spotlight away from the ‘natural’ components. This shows that the idea that “For many Americans wilderness stands as the last remaining place where civilization, that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth” (Cronon 1) is not how nature is used in artificial islands in Qatar. If Banana Island wanted to promote the ‘natural’ aspects of the resort that picture would only have the ocean and the sky in it, because Banana Island would want you to feel humbled by the ‘sublime’. But the images consider the boardwalk more important, that is why it is in the middle. Thus, one can see why many of the artificial islands describe themselves with the word ‘luxury’ as promotion. The image of the “Q Lounge & Restaurant” shows that the ‘luxury’ of artificial islands is the fact that they provide one with the “freedom and independence” (Bergthaller 429) that “became fully identified with individualized control over one’s private circumstances” (Bergthaller 429). Bergthaller wrote this line commenting on Huber talking about how energy usage being convenient became normal in “the “American Way of Life”” (Huber 17, quoted in Bergthaller 429). That people can do many different things on the island, amenities that are all human-made, while enjoying the sight of the ocean and the sky is what ‘luxury’ is in these artificial islands. That is why the human-made aspects are in the middle of that photograph in Banana Island’s gallery and also that picture of Costa Malaz in The Pearl. It is because they are more important, the feeling of freedom mentioned in Bergthaller’s book chapter that people feel having convenience with energy usage is more important. ‘Natural’ aspects are not ‘sublime’ in artificial islands in Qatar, they are the ornaments, the bonuses of the human-made aspects. The quote that Cronon used that was mentioned previously explains that nature was considered someplace void of human-made components for several Americans (Cronon 1). The way that Qatar’s artificial islands advertise themselves shows that this is not how they see nature, and that it is not ‘sublime’.

In conclusion, ‘luxury’ in Qatar’s artificial islands highlights that Cronon’s ideas are not applied to them, but that Bergthaller’s ideas are. The promotional picture of the boardwalk on the beach in Banana Island takes the expansiveness of ‘nature’ from Cronon and merges it with the freedom from convenience of energy usage from Bergthaller. The way that it was done showed which was the true point of advertisement for the island. However, I would like to point out the same question I had in my last blog post at the end of this one. I am still interested to know what it means to feel that freedom when energy becomes convenient at home, versus a resort. The latter is a temporary place, and, if one were to assume that the ‘luxury’ it has is more than what one would have at home, then that should mean the energy convenience at the resort allows you to do more or do the same things in a more decadent place. This topic introduces questions on the psychology of energy addiction in a place of ‘luxury’ and a place that is not like that.

Works Cited

Bergthaller, Hannes. “Fossil Freedoms: The politics of emancipation and the end of oil.” The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities. Edited by John Christensen, Ursula K. Heise and Michelle Neimann, London: Routledge, 2017, 424-432.

Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness.” Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, New York: W.W Norton & Co., 1995, 1 – 24.

Huber, Matthew T. Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota University Press, 2013. Print. Quoted in Bergthaller, Hannes. “Fossil Freedoms: The politics of emancipation and the end of oil.” The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities. Edited by John Christensen, Ursula K. Heise and Michelle Neimann, London: Routledge, 2017, 424-432.