First of all, I’d like to acknowledge the value of the initiative “Doing Environmental Humanities in Doha” brought by the course of Environmental Humanities that inspired us to ask questions on the matters of ‘nature’, ‘ecology’, ‘modernity’, ‘energy’, ‘capital’ and ‘humanity’ that were in our minds, somewhere in the background, undiscussed. Within the framework of ecocritical theories, we engaged in conversations on human exceptionalism, petroculture, nature-culture dichotomy, ecofeminism, posthumanism, eco-Marxism, environmental justice, and apocalypse. From all of these, I found the relationship between humans and non-humans exciting and provoking. For the first time, I had the forethought to care about the ecosystem’s point of view concerning humans.

This eventually led to the question of how to keep a balance between the significance of humanity and of ecology and how both of these could coexist in harmony. Many experts in the field of environmental humanities have already contemplated a lot about “the representation of non-human”. From the perspective of the history of science, scholars like Lorraine Daston were skeptical of the mobilization of nature for symbolic representation of human practices, social norms, and morality. She mainly argued to question the adaptation of norms and values from the realm of ‘natural’ because she found neither ‘specific natures’ nor ‘local natures’ the adequate source for the organization of human norms and morality. In the “Public Art” initiative I chose the ‘Falcon’ sculpture by Tom Claasen in Doha, and argued that exploiting non-humans by using the symbol of the falcon as a symbol of Qatar’s aviation industry ‘naturalizes’ the hazardous environmental externalities caused by air travel. Daston’s argument was helpful in raising questions about the sculpture and examining the symbolism of the nature-culture relationship and continuation of the falcon’s experience of flight. We should be skeptical of the mobilization of the natural because Daston made it clear that ‘natures’ in the non-human world don’t resemble the same norms and values humans possess.

Biodiversity scholars like Ursula K. Heise questioned the effectiveness of allegory in representing the environment and argued that we should seek for alternative representations to capture both human heterogeneity and harmony of the global ecology. Ursula argued allegory has infiltrated the global environmental imagination and thought and that we should seek representations more complex than allegory which could “accommodate social and cultural multiplicity”. For example, by the allegory of the global, Heise suggested the Gaia hypothesis and the blue marble image. The allegory represents the world as simple and whole, while neglecting the complexities important to capture ecological connectedness and cultural heterogeneity at the same time. I used her skepticism of allegory and its alternative representations to analyze the complex system of human-sea relationships represented by the sculpture ‘Gates to the Sea’ by Simone Fattal in Doha. Even though the sculpture doesn’t contain the allegory of the global, it is open to Heise’s criticism because it’s a broad allegory of national history. While trying to imagine the connection between the past of pearl fishing and the intimate relation with the ocean led to continuous development and the petromodern present, some degree of cultural complexity and environmental conflict gets elided. The sculpture seems to be constructed on a positive note and abandoning the environmentally hazardous events, implying that human’s relationship with the sea was continuously benevolent and extraction of sea resources like pearl, oil, and gas didn’t cause any disturbance for marine life. There is some doubt in this optimistic view, as both in the past and now there is a threat to coral reefs and the risk of oil leakage.

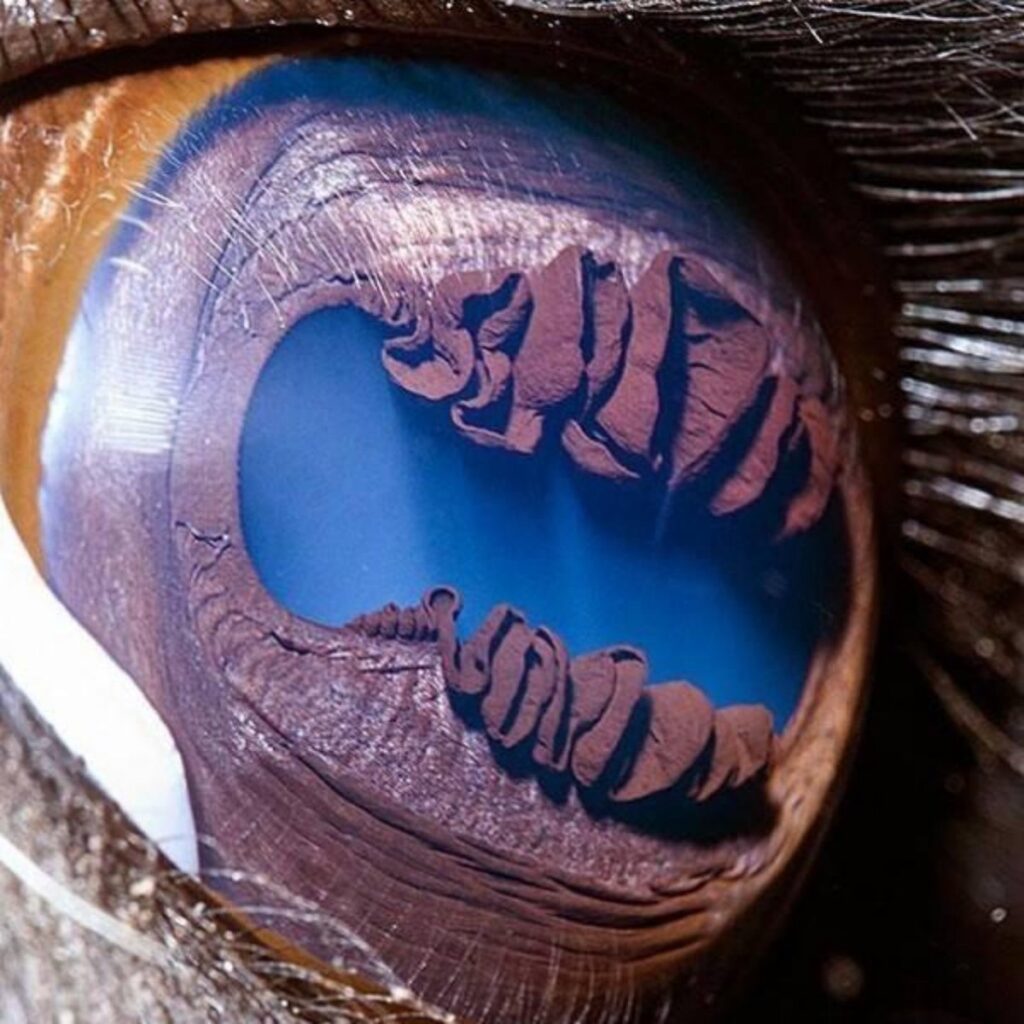

Eduardo Kohn, an anthropologist, argues in his well-known book “How Forests Think” that it is important to recognize that non-human beings have their own perspectives on the human world. According to him, the logic of form governs the logic of living thinking, and the brains of humans and other species are distinct in how they see the world and how they express it. He wondered what would happen to thought if it was free from intention. It is impossible to morph into other forms and we could only imagine the perspective of that form looking at us and visualizing the human world from its point of view. Another living form has a different world vision due to differences in the sense of perception, level of salience, consciousness, memory capacity, and brain complexity. So, in an attempt to acknowledge the point of view of animals concerning us, it’s our obligation to study the features of the form of thinking and be transparent and accountable as much as possible in displaying them accurately in environmental humanities. If in literature these features could be described, explained, and comprehended in a written text, what are the implications for the visual text present in arts? What are the ways in which the artist should represent the non-human world and avoid attaching anthropocentric views and meaning to his/her work of art? Compared to interacting with a living animal, what are the challenges in interacting with the human-made sculpture? And the question emerging from the previous is how could we make the interaction with the work of public art more engaging and insightful than the interaction with the animal. I explored the sculpture “On Their Way” created by Roch Vandromme in Doha which depicts the dynamic and intimate relationship between humans and camels. The magnificent sculpture of two calves and two mature dromedaries stands near National Museum for families with their children to interact with. Even though the sculpture allows people to appreciate the beauty and elegance of camels and recognize the animals as the life companions of past and present, the sculpture seems to exclude the camel’s point of view. Kohn’s anthropocentric narcissism is openly manifested in this one-way interaction where the visitor interacts with the sculpture of the camel but receives no feedback from the sculpture. At the same time, the visitor leaves the sculpture without acknowledging the camel’s point of view and without imagining how the camel would perceive the human in the camel’s eyes. Kohn’s logic of forms explains the drastic difference in thinking and world vision between human and non-human living forms. Kohn would argue for the acknowledgment of the camel’s point of view in the ‘On their way’ sculpture.

In order to encapsulate the camel’s point of view, one of my suggestions is to install video cameras in the camel’s eyes and broadcast the live video on the screen near the sculpture. It’s also possible to put the camera filters to integrate the features of the camel’s vision: add a translucent layer to imitate the third eyelid which is thin enough to allow the camel to see even when the eyes are closed. To replicate this, the camera can adjust the shutter speed option to imitate the eyes closing when the camel is blinking and at the same time leaving available light reaching the lens to make the image translucent. Also, the video can have a filter with sand flowing into the camel’s eyes, then the camera shattering and opening back to mimic the eyelid working as a windshield wiper to remove the sand. Also, the upper part of the video can display large and long lashes to simulate the lashes on the upper eyelid that camels have. All of these effects together with the video could be translated onto the screen visitors are looking at. This might allow seeing our reflection, the image of ourselves projected through the perspective of the camel’s point of view. I believe that this kind of technological enhancement might help us approach public art in a more accountable way making the representation of non-humans less anthropocentric.

In furtherance of the project on the representation of non-humans in public art, I would like to work more closely with the public art presented by Qatar Museums. After investigating the works of public art such as ‘Falcon’, ‘The Gates to the Sea’ and ‘On their Way’, I found out, as I mentioned earlier, these are constructed on a positive note, mobilizing, using, adapting, and integrating nature for the optimistic display of human life, history, practices, norms, and values. In order to avoid one-way interaction with public art, I suggest that the subject of the sculpture should be able to interact with the human as well. This could be done at least through the visual feedback which I suggested for the sculpture ‘On their way’, so visitors can perceive themselves through the subject’s POV. I think the ambition to capture the vision of animals through public art could invite not only artists and experts from environmental humanities but also animal scientists to work on it.