Environmental humanities is an interdisciplinary field that employs distinct humanistic studies about natural world and the role of humans living in it with a view to looking at ranges that are far beyond literary studies. As per Qatar, there are numerous public arts installed that can potentially be linked to environmental humanities, such as Force of Nature, On their Way, Falcon, Gates to the Sea and many more, because the study of these public art installations indeed allows us to recognize the interdisciplinary nature of the message that they are trying to convey. This course indeed inspired me to analyze the relationship between the human and nonhuman world through a comparative environmental study of public art installations in Qatar; and also led me to a question “Though these sculptures might meticulously showcase the relationship between the human and nonhuman world, to what extent are they considering their own interests/benefits or how far it is more of an anthropocentrism rather than an even balance of both human and nonhuman world?”

The significance of modern and contemporary public art installations in Qatar lies in internalizing an ecological responsibility through the power of art, but at the same time bringing out the depiction of the national representation. As for the public art installations, most of them were created by foreign artists, where the sculptures intently showcase the relationship between the natural world and human world, but the overarching theme of anthropocentrism is still vividly conspicuous. Therefore, in my final brief, I will explore the potential grounds and motivation of these foreign artists establishing their artwork in Qatar with ecological consciousness, while at the same time depicting the national representation or identity, which definitely counterbalances the anthropocentrism over biocentrism.

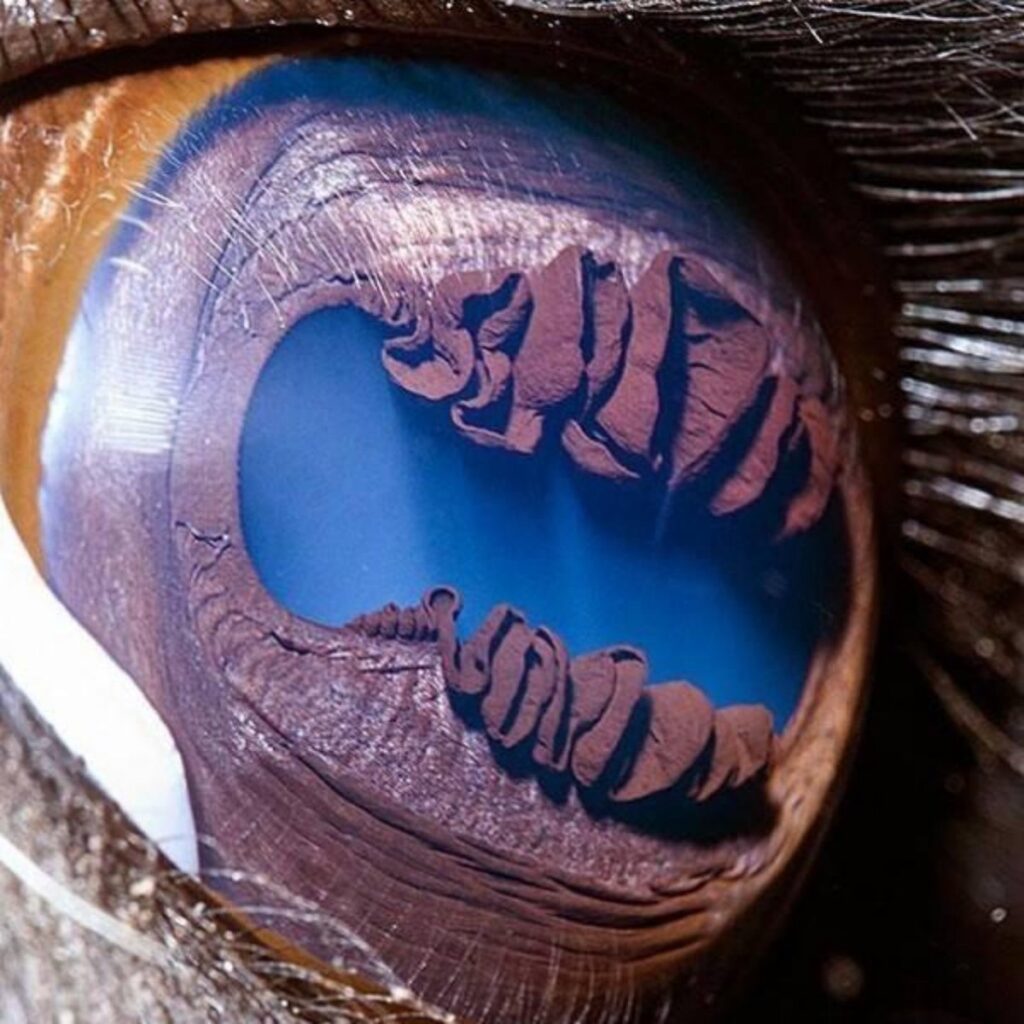

For instance, in the case of “Falcon”, it is known to be one of the renowned public art installations in Qatar that was created by a Dutch sculptor, Tom Claassen. He made this sculpture with a view to portraying the significance of nature and wildlife by an abstract representation of Qatar’s national bird. This immediately brings forth the book “How Forests Think” by Eduardo Kohn, where he explicitly enforces the readers to step out of an anthropocentric perspective, re-think and re-evaluate humans’ actions. It is because the scholarship of this book indeed responds to the sculpture “Falcon”, as it shows the falcon merely as a human activity and ‘almost’ camouflages the true identity of the bird and its intrinsic value in nature. As an illustration, the falcon is covered in a fabric of Qatar’s traditional attire and the lines/curves on its feathers are found in the Arabic calligraphy; which definitely serves the purpose of representing the national identity of Qatar but again does it really depict the wildlife in its natural habitat?

Building up the argument, there is another secondary source “What is Posthumanism” by Cary Wolfe, who also supports the claim that the topic of anthropocentrism is a problematic position. And as the title of this book already suggests, Wolfe is also seeking to find an answer for ‘posthumanism’; but most importantly can this new kind of philosophical perspective respond to both the technological and environmental continuum in the long run?

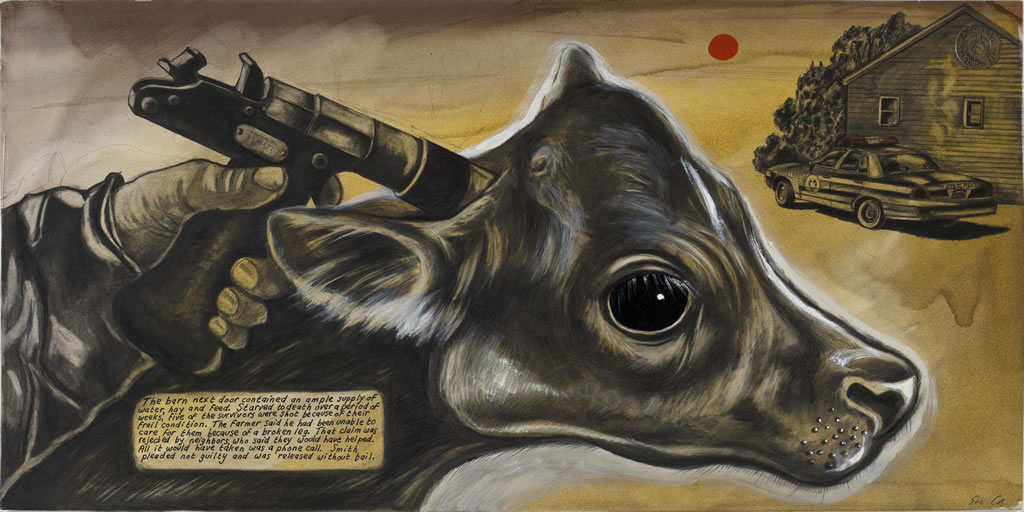

Furthermore, with respect to the artworks made by Sue Coe that essentially include animal rights commentary and are portrayed powerfully in showing the scenes of animal suffering, there are some critiques made about her artwork. For instance, Cary Wolfe openly extended his response to Sue Coe’s artwork, explicitly stating that her artwork’s representational choices should be far more significant than the impact it has on the audience. And this entails the fact that Wolfe is more interested in physical representation of the artwork rather than the contextual representation, because Wolfe sees Sue Coe’s artwork not only anthropocentric but also “committed to this posthumanist question in a humanist way”. Now, linking it back to the sculpture “Falcon”, I can still criticize it the same way Wolfe did to Coe’s artwork. As a matter of fact, the falcon acts as a metaphor representing the national identity of Qatar as well as ‘allegedly’ depicting the wildlife. However, I as an audience along with Wolfe, we do not look for ‘metaphor’ or the hidden message behind the sculpture, but rather the representational choices and the artistic intentions of the artwork. Seeing that Tom Claassen aimed to create this sculpture with an intention of representing the natural wildlife, he should have let the falcon exhibits its authenticity in its true natural habitat, in order to give importance to its intrinsic value. But unfortunately, from the audience’s perspective, the first thing we see is the golden coverage that immediately evokes the atmosphere of royalty, rather than nature or environment. And second, the facial expression of the falcon is not visible at all – stressing on the fact that the falcon as a bird is barely significant. Thus, this conspicuously shows that the sculpture “Falcon” is subtly regarded as a human activity that attracts the audience as an object or a simple sculpture, instead of actually ‘showing’ the true colors of the falcon.

Nonetheless, in order to strengthen my argument, this final brief will look into another public art installation in Qatar that can contribute to the claim from a different angle. “On their Way” is another sculpture that was made by a French artist Roch Vandromme, which vividly mirrors the enriching culture of Qatar comprising the figure of four camels that represent the continuation of the dynamic relationship between humans and camels. In this case, Vandromme dedicated his work for the camels in their natural habitat, and the sculpture as a whole is indeed an embodiment of portraying Qatar’s long history of nomadic lifestyle and the human-camel progressive relationship over the course of time. Thus, we can see that there is an even balance of depicting the national representation/identity as well as providing equal acknowledgement for the natural world. It is because this can be deduced from the absence of humans that infers the rejection of ‘human exceptionalism’ – also highlighting the fact the sculpture is not anthropocentric at all.

As mentioned earlier, Vandromme depicts the camels in their natural habitat – and this is vivid from the fact that there are two calves and two mature camels standing very ‘naturally’, but most importantly their facial expressions are very clearly shown. This again actively demonstrates that the representational choices of Roch Vandromme were very deliberate and, henceforth this counterclaims the argument “we cannot see as much as we think we can” made by Cary Wolfe. The sculpture indeed responds to this statement by Wolfe, because as an audience we can clearly see the facial expressions, body language and the significance of the camels immediately, rather than attempting to seek the hidden message or the metaphor behind it. That is why, this sculpture by Roch Vandromme, a foreign artist, certainly proved to depicting the national representation/identity as well as gave equal importance to both human activity (the sculpture itself) and the natural world (the camels in their natural habitat).

All in all, through the analysis of these public art installations in Qatar and linking them with secondary sources from distinct fields of study indeed gave me an exposure of exploring environmental humanities overall. And I believe that Qatar intentionally gave the opportunity to foreign artists, in order to invest in Qatar’s arts in general, with a view to holistically represent Qatar’s identity as well add their ‘own’ contribution and motivation, whether it is environment-related or history-related. However, as I was closely arguing that the grounds and motivation of foreign artists is not only creating their work for national representation, but with a strong ecological consciousness, where the concept of anthropocentrism is very limited. As seen from the sculptures discussed above, some of them are merely serving the purpose of ‘being a metaphor’ for some hidden meaning and very less thought is provided on the artwork itself. While others are very deliberate with the minute details of the artwork and the audience is undoubtedly convinced with the representational choices of the work made by the artist.

“I want my monumental works to have even more of an effect on the public. The moment the sculpture enters the common space, it is no longer mine. My ownership ceases and it becomes the people’s.”

– Lorenzo Quinn