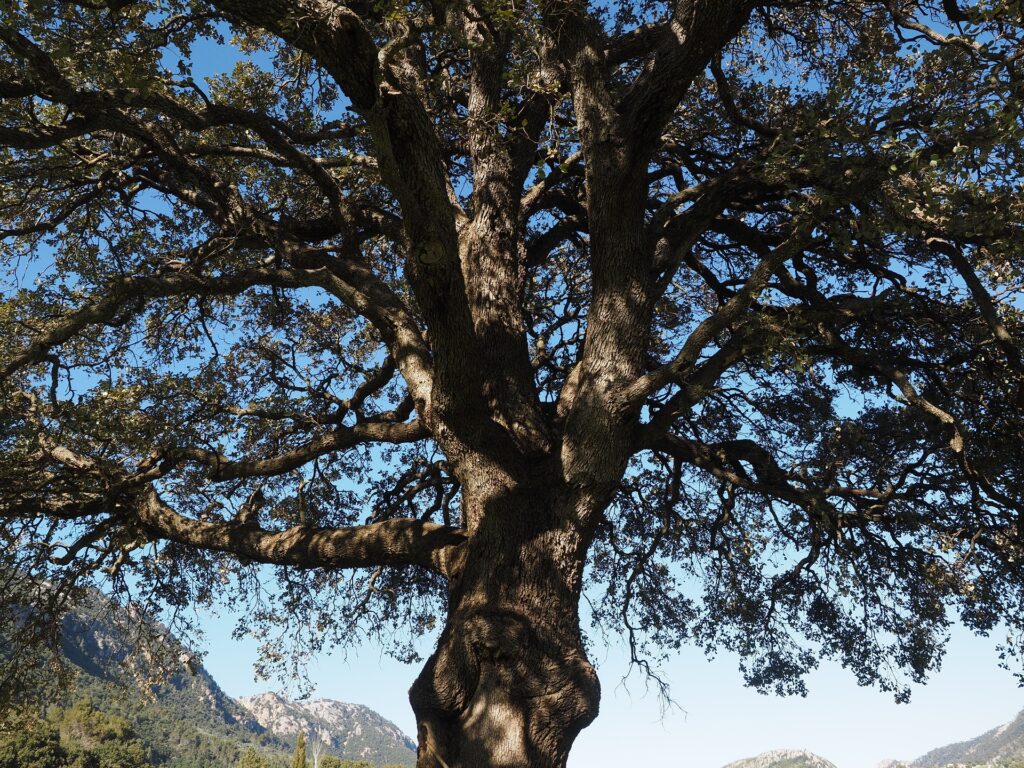

Date Palm Tree | النَّخيل

——————————

Significance:

There are many instances where palm trees are mentioned in the Quran. However, most notably, it is mentioned in Surah Maryam, when God orders the archangel to convey a message to Maryam (Mary):

“So she carried him, and secluded herself with him in a remote place. (22) The labor-pains came upon her, by the trunk of a palm-tree. She said, “I wish I had died before this, and been completely forgotten.” (23) Whereupon he called her from beneath her: “Do not worry; your Lord has placed a stream beneath you. (24) And shake the trunk of the palm-tree towards you, and it will drop ripe dates by you.” (25)”

[Maryam: 22-25]

——————————

Note: Image is courtesy of Pixabay. Information courtesy of the QBG.

——————————

Significance:

Figs are mentioned in the Quran, notably in Surah Al-Tin, whereby God swears by the Tin:

“By the fig and the olive.”

[Al-Tin: 1]

——————————

Figs are displayed near the Play Bowl.

Note: Image is courtesy of Pixabay. Information courtesy of the QBG.

——————————

Significance:

Olives are mentioned six times throughout the Holy Quran. Notably, it is symbolically used in the following verse from Surah An-Nur:

“God is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The allegory of His light is that of a pillar on which is a lamp. The lamp is within a glass. The glass is like a brilliant planet, fueled by a blessed tree, an olive tree, neither eastern nor western. Its oil would almost illuminate, even if no fire has touched it. Light upon Light. God guides to His light whomever He wills. God thus cites the parables for the people. God is cognizant of everything.

[An-Nur: 35]

——————————

Olives are displayed near the Play Bowl.

Note: Image is courtesy of Pixabay. Information courtesy of the QBG.

——————————

Significance:

Camphor is mentioned once in the Holy Quran, notably as a reward for the virtuous upon entering paradise:

“Indeed, the virtuous will have a drink ˹of pure wine˺—flavoured with camphor.”

[Al-Insan: 5]

——————————

Camphors are displayed near the Play Bowl.

Note: Image is courtesy of Pixabay. Information courtesy of the QBG.

Botanical Gardens Throughout History

The mission of the Western and European botanical gardens is to increase people’s understanding of the intrinsic values of plants. It has done this through developing educational programs, the exhibition and interpretation of collections, and conducting relevant research (Rakow and Lee 269). Cohen and Foote (162) stated that much of the nineteenth century saw significant European botanical gardens gathering specimens from colonies and displaying them as indicators of the scope of their imperial power and advancing their goals.

In contrast to imperialist gardens that served colonial purposes, the Quranic Botanic Garden (QBG) in Qatar is the first of its kind in the world. Its promotion and safeguarding of the natural, cultural, and spiritual legacy of Islam and Arab states in a broader global context has provided creative opportunities for learning and exploration and is an overall innovative use of botanical gardens. The primary emphasis of the Garden is to explore the traditional uses of plants, their purposes in human existence, and long-term, sustainable methods of employing such plants, all with the overarching goal of reviving the cultural tradition. The Garden seeks to amass examples of these cultural artefacts from around the globe so they may be displayed at the local Botanical Museum.

It is important to note that one of the primary missions of the QBG is to identify and catalogue the various plants and botanical terms mentioned in the Holy Quran and Hadith. This is crucial to conserving Islamic culture and plants because despite their presence in the Quran and other Islamic scriptures, many Muslims, even self-proclaimed religious experts, are unfamiliar with their significance (Zeerak 108). Therefore, classification is an essential part of the study of their biodiversity.

Datson’s Against Nature

Various scholars have presented their theories and definitions of ‘nature’; the most common is ascribed as the essence of a thing or everything in the universe. The definition of nature has resulted in the derivative the “natural”. However, in defining nature, Daston (6) chooses to define it in the context of ‘specific nature’ and ‘local nature’. Specific natures embrace the characteristic forms of things, their properties, and their tendencies (Datson 7), while local natures “are about the power of place” (Datson 15).

Daston invokes the human sensorium, or our ability to sense the “surface of things” (Datson 59). She refutes the concept that drawing standards from nature lead to a conservative interpretation of norms: rules that are permanent rather than flexible, transcendental rather than customary, and universal rather than situational. The views propagated by Daston are different from those of the QBG in the sense that the Garden promotes an essential Islamic worldview, promoting awareness of the Creator and the created through environment and conservational means. However, the garden promotes the idea that humans can articulate and support moral norms concerning nature. The ‘natural’ anticipated in the QBG is one in which humans can interact and derive moral values, which is against what Daston contends. Daston admits that we may define and maintain our moral principles without referring to nature since alternate order instances exist within human civilisation, such as mathematics, technology, or the arts. This implies that to Daston, ‘natural’ is intractable and cannot be changed and that defying nature could result in failure. Therefore, the QBG defies nature from the religious perspective as it goes against Daston’s argument.

Works Cited

- Cohen, Jeffrey and Foote Stephanie. “The Cambridge companion to environmental humanities.” Cambridge University Press, 2021, https://www.cambridge.org//academic/subjects/literature/literary-theory/cambridge-companion-environmental-humanities?format=HB&isbn=9781316510681

- Daston Lorraine. “Against Nature.” MIT Press, 2019.

- Rakow Donald A. and Lee Sharon A. “Western botanical gardens: History and evolution.” Horticultural Reviews, vol. 43, no. 1, 2015, pp. 269.

- Sessions George. “The third world, wilderness, and deep ecology.” Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: Readings on the Philosophy and Practices of the New Environmentalism, 1995.

- Zeerak Nazir Ahmed. “The Qur-ānic plants and animals.” New India Publishing Agency, 2015.